On the surface, a landfill is a place to dispose of waste. But from an engineering and environmental protection standpoint, not all landfills are created equal. The type of waste being contained dictates every single aspect of the facility's design, from the materials used to the long-term monitoring required. Confusing the requirements for a Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) landfill with those for a Hazardous Waste (HW) landfill can lead to catastrophic environmental failure and immense legal liability.

As specialists in geosynthetic containment, we’ve seen firsthand how these differences play out in the field. This guide is designed to provide a comprehensive, detailed comparison between MSW and Hazardous Waste landfill design. We will dissect the granular differences in regulatory frameworks, liner systems, material specifications, quality control, and long-term care to give you a clear understanding of why these two types of facilities are fundamentally different engineered structures.

The journey begins with the most fundamental distinction of all: the design philosophy, which is driven by the nature of the waste itself.

1. Functional Purpose and Regulatory Framework

The most critical difference between an MSW and a Hazardous Waste landfill lies in their core design philosophy, which is a direct reflection of the waste they accept.

MSW Landfill: Stabilization Over Time

An MSW landfill is designed based on a stabilization model. It primarily accepts household trash, commercial waste, and other non-hazardous materials. A significant portion of this waste is organic. Over decades, this organic material undergoes anaerobic decomposition, gradually breaking down and stabilizing. The leachate produced is most concentrated in the early years and its toxicity generally decreases over time as the waste mass stabilizes. The primary environmental risk, while significant, has a finite peak and a projected decline.

Hazardous Waste Landfill: Permanent Isolation

A Hazardous Waste landfill operates on a completely different principle: permanent isolation. The wastes it accepts—toxic chemicals, heavy metals, solvents, reactive by-products—do not stabilize or become less hazardous over time. Their dangerous characteristics can persist for centuries, if not millennia. Therefore, the landfill is not designed to treat or stabilize the waste, but to entomb it and permanently isolate it from the environment. The risk profile is constant and unending.

This philosophical difference is codified in distinct regulatory frameworks. In the United States, for example:

- MSW Landfills are governed by RCRA Subtitle D, which sets minimum national criteria for non-hazardous solid waste facilities.

- Hazardous Waste Landfills must adhere to the far more stringent regulations of RCRA Subtitle C, which mandates a "cradle-to-grave" system of control for hazardous materials, including their final disposal.

Every design and material difference that follows is a direct consequence of this core principle: one system manages a declining risk, while the other must contain a permanent one.

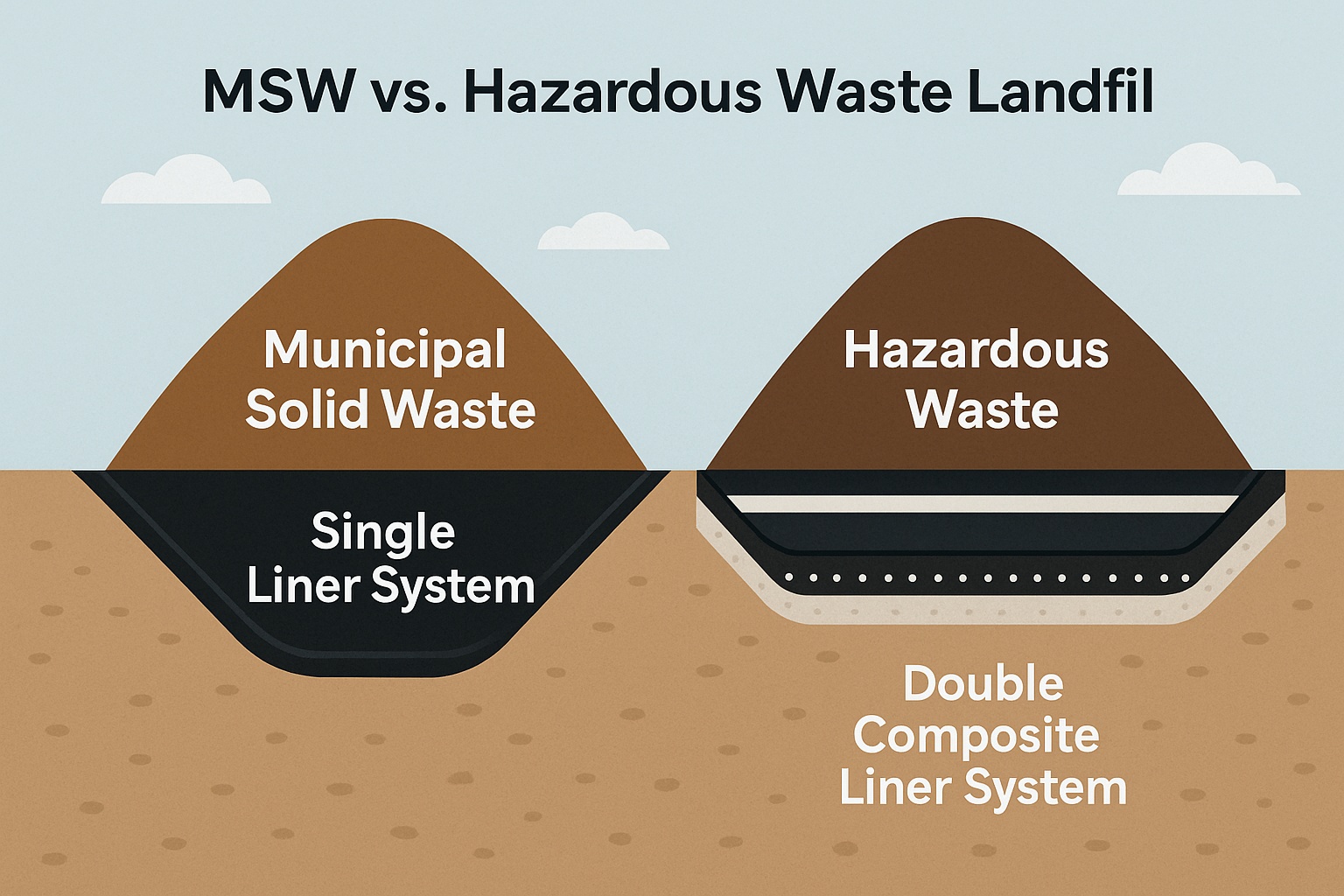

2. Liner System Design Requirements

The liner system is the heart of any landfill, and it is where the design differences are most pronounced.

MSW Landfill Liner System

A typical MSW landfill today uses a composite liner. This system consists of two distinct layers working together:

- A geomembrane: Usually 1.5 mm (60 mil) HDPE.

- A low-permeability soil layer: Either a 60 cm (2 ft) thick layer of compacted clay (with a permeability of ≤ 1x10⁻⁷ cm/s) or a Geosynthetic Clay Liner (GCL).

While some jurisdictions may require a double liner for added security, a single composite liner is often the regulatory baseline.

Hazardous Waste Landfill Liner System

For a Hazardous Waste landfill, a double composite liner system is mandatory. It is a multi-layered, redundant system designed for maximum security:

- Primary Liner (Top Layer): A thick HDPE geomembrane (often 2.0 mm to 2.5 mm) in direct contact with a GCL or thick compacted clay layer. This is the primary barrier.

- Leak Detection System (LDCRS): A drainage layer (geonet or gravel) located directly beneath the primary liner. Its sole purpose is to collect any liquid that might breach the primary liner, proving that the primary containment is working and allowing for rapid response if it is not.

- Secondary Liner (Bottom Layer): A second, independent composite liner (geomembrane and clay/GCL) that acts as a final fail-safe.

The key here is redundancy. The hazardous waste design assumes that the primary liner could eventually fail and provides an entire, independently monitored secondary system to prevent an environmental release.

3. Geomembrane Selection and Thickness Differences

The choice of the geomembrane itself reflects the different chemical environments.

MSW Geomembrane

For MSW landfills, standard-grade HDPE (High-Density Polyethylene) is the material of choice due to its broad chemical resistance, durability, and cost-effectiveness. A thickness of 1.5 mm (60 mil) is the common industry standard.

Hazardous Waste Geomembrane

Hazardous Waste landfills demand a higher level of performance.

- Thickness: The minimum thickness is often increased to 2.0 mm (80 mil) or even 2.5 mm (100 mil) to provide a greater safety margin against physical damage and chemical diffusion.

- Resistência Química: The HDPE resin formulation may be specifically selected for its enhanced resistance to aggressive chemicals, solvents, or extreme pH levels found in the specific waste stream.

- Material Specifications: Technical specifications are stricter. For example, a hazardous waste geomembrane might require a higher tensile strength (e.g., ≥16 MPa vs. ≥15 MPa), greater elongation (≥700% vs. ≥600%) for better toughness, and a higher carbon black content (≥2%) for superior UV resistance during installation. Only 100% virgin resin is permitted, with no tolerance for recycled materials.

4. GCL and Clay Barrier Requirements

The soil component of the liner is just as critical.

MSW Clay Barriers

An MSW landfill liner will include either a Forro de argila geossintética (GCL) or a Compacted Clay Liner (CCL) typically around 60 cm (2 ft) thick. The goal is to achieve a hydraulic conductivity (permeability) of no more than 1x10⁻⁷ cm/s.

Hazardous Waste Clay Barriers

The requirements for a Hazardous Waste landfill's soil barrier are substantially more robust. A typical secondary liner might require a CCL that is 1 meter (3 ft) thick or more. Some designs call for even thicker layers (up to 4.5 m was mentioned in one study) to provide an incredibly long travel time for any potential contaminants. While the permeability requirement of ≤1x10⁻⁷ cm/s is the same, the quality control and verification process is far more intense, with in-situ testing performed across the entire liner area, not just in representative samples.

5. Leachate Collection and Drainage System Differences

Both landfill types need to manage leachate, but the systems are designed with different levels of urgency and material requirements.

MSW Leachate Collection

MSW landfills feature a primary leachate collection system above the liner. It typically consists of a 30 cm drainage layer of gravel or a high-flow drainage geocomposite, with perforated pipes to transport the leachate to a sump. The regulatory limit for leachate head on the liner is universally 300 mm (1 ft).

Hazardous Waste Leachate and Leak Detection Systems

A Hazardous Waste landfill has two separate drainage systems:

- Primary Leachate Collection System: Located above the primary liner, this system is similar in function to the MSW system but is often built with more robust, chemical-resistant materials.

- Leak Detection, Collection, and Removal System (LDCRS): This is a full drainage layer located between the primary and secondary liners. Its job is not to manage bulk leachate but to detect and remove even trace amounts of liquid that might get through the primary liner. The presence of any significant liquid in this layer triggers an immediate response. The 300 mm head limit is an absolute maximum that must never be approached, requiring 24/7 pumping capabilities.

6. Gas Management System Differences

The gas produced by the two types of waste is fundamentally different.

MSW Landfill Gas

MSW contains a high percentage of organic material that decomposes to produce large quantities of landfill gas (LFG), which is roughly 50% methane (CH₄) and 50% carbon dioxide (CO₂). This gas is flammable and a potent greenhouse gas, so active gas collection systems are mandatory. These systems use a network of wells and pipes to extract the gas, which is then either flared or used to generate energy.

Hazardous Waste Landfill Gas/Vapor

Hazardous waste is typically inorganic and does not undergo significant biological decomposition. Therefore, it produces minimal methane. The concern is not flammable gas but the potential release of toxic volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and other hazardous vapors. Gas management focuses on containment via an impermeable final cover system, rather than active collection and treatment.

7. Cover System and Closure Design

The final cover, or "cap," is designed with the same philosophy as the liner: stabilization vs. permanent isolation.

MSW Cover System

An MSW cover is designed to minimize water infiltration, control gas escape, and promote vegetation. It's a multi-layer system but is ultimately designed to be part of a stabilized landscape that could one day be repurposed as a park or golf course.

Hazardous Waste Cover System

The hazardous waste cover is a permanent containment barrier. It is significantly more complex and robust, often mirroring the bottom liner system. It must be designed to prevent water ingress and vapor escape for centuries. It may include its own geomembrane vapor barrier, a GCL, drainage layers, and thick soil layers to protect the barrier components from freeze-thaw cycles and root penetration. The site will be permanently restricted from any future use.

8. Monitoring, QA/QC, and Long-Term Care Requirements

The level of oversight during and after construction reflects the level of risk.

MSW Monitoring and Care

Monitoring involves periodic groundwater sampling (e.g., semi-annually), inspections, and managing the leachate and gas systems. Post-closure care typically lasts for 30 years in the U.S.

Hazardous Waste Monitoring and Care

This is a far more intensive and perpetual commitment.

- Groundwater Monitoring: Wells are more numerous and sampling is more frequent (e.g., quarterly or monthly). The list of chemicals being tested for is extensive.

- LDCRS Monitoring: The leak detection system is monitored continuously or daily. Any liquid collected is measured and tested immediately.

- Post-Closure Care: This is effectively in perpetuity. The operator is responsible for maintaining and monitoring the site forever, as the waste will never become non-hazardous.

9. Construction Quality Requirements and Material Handling

The difference in risk tolerance translates directly to construction practices.

MSW Construction Quality

Construction Quality Assurance (CQA) is standard practice. It involves third-party oversight to ensure materials meet specifications and installation follows best practices. Geomembrane welds are tested using a combination of non-destructive and destructive methods on a specified frequency.

Hazardous Waste Construction Quality

CQA for a hazardous waste site operates on a "zero-defect" policy.

- Inspection Intensity: Oversight is continuous. Every truckload of soil, every roll of geomembrane, and every step of the installation process is documented.

- Welding Inspection: 100% of geomembrane seams are non-destructively tested (e.g., with air pressure or vacuum box). Destructive testing frequency is much higher (e.g., one sample every 150 meters of weld).

- Earthworks: Standards for subgrade preparation are higher, requiring greater compaction (e.g., ≥95% max dry density) and a surface completely free of any sharp objects.

10. Cost Implications and Engineering Complexity

Unsurprisingly, the vast differences in design, materials, and oversight result in a huge cost differential. A Hazardous Waste landfill is an order of magnitude more complex and expensive to design, build, and operate than an MSW landfill. Sources estimate the capital and operational costs can be 2 to 3 times higher, or even more. This cost reflects the price of permanent, secure containment and the immense liability associated with managing materials that pose a perpetual threat to human health and the environment.

11. Summary: Choosing the Correct Landfill System Based on Waste Type and Risk Level

The decision of which system to use is not a choice but a mandate dictated by the waste's characteristics. Here is a summary of the key differences:

| Feature / Component | MSW Landfill (RCRA Subtitle D) | Hazardous Waste Landfill (RCRA Subtitle C) |

|---|---|---|

| Design Philosophy | Stabilization over time | Permanent Isolation |

| Liner System | Single composite liner (geomembrane + clay/GCL) | Mandatory Double Composite Liner with Leak Detection |

| Geomembrana | 1.5 mm (60 mil) standard HDPE | 2.0-2.5 mm (80-100 mil) HDPE with enhanced chemical resistance |

| Leachate System | Single leachate collection layer | Two separate systems: Primary collection and a mandatory Leak Detection System (LDCRS) |

| Gas Management | Active methane gas collection | Containment of toxic vapors; minimal methane |

| Final Cover | Water barrier, supports vegetation | Permanent, multi-layer containment barrier |

| Construction QA/QC | Standard CQA, statistical testing | Intensive CQA, "zero-defect" policy, 100% seam testing |

| Post-Closure Care | 30 years (typical) | Perpetual, indefinite care and monitoring |

| Overall Cost | Baseline | 2-3x or more than baseline cost |

Ultimately, the engineering principle is clear: you must build the containment system to meet the demands of the waste. For municipal solid waste, this means a robust system designed for a long but finite service life. For hazardous waste, it means building a fortress designed to last forever.