When a project requires a robust, self-healing hydraulic barrier, Geosynthetic Clay Liners (GCLs) present a state-of-the-art solution. But what gives this engineered composite its remarkable sealing power? The secret lies in a special type of natural clay, and not all clays are created equal.

This technical guide uncovers the principles behind GCLs, starting with their most critical component: the bentonite. We will explore why the type of clay matters, how it works, and the essential construction requirements needed to ensure your GCL installation provides a permanent, leak-free containment system.

Understanding this material is key to a successful application. A GCL is more than just a waterproof blanket; it's a reactive system that demands precise handling and installation. Let's delve into the core of what makes it work.

Sodium vs. Calcium Bentonite: The Heart of the GCL

The performance of a GCL is dictated by its primary mineral component: montmorillonite, commonly known as bentonite. However, natural bentonite exists in two main chemical forms: sodium-based and calcium-based. Their difference in performance is dramatic and is the single most important factor in choosing a high-performance GCL.

- Calcium Bentonite: When exposed to water, calcium-based bentonite has a limited swell potential, typically expanding to only about three times its original dry volume.

- Sodium Bentonite: In contrast, sodium-based bentonite is a super-absorbent. It can swell to approximately 15 times its original volume and absorb up to six times its own weight in water.

This massive swelling potential is what makes sodium bentonite the superior choice for waterproofing. As it hydrates, the individual clay platelets separate and form a dense, gel-like substance with extremely low permeability. For this reason, high-performance GCLs exclusively use sodium bentonite as their sealing core.

| Bentonite Type | Swell Volume | Water Absorption | Permeability | Application Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| بنتونيت الصوديوم | ~15x original volume | ~6x its weight | Extremely Low (Ideal for sealing) | Primary choice for GCLs, landfills, reservoirs, critical containment. |

| Calcium Bentonite | ~3x original volume | Low | Moderate to High | Rarely used for waterproofing; more common in agriculture or as a binder. |

How a GCL Works: The Swelling and Sealing Mechanism

Now that we've established sodium bentonite as our active ingredient, how does it function within a GCL? The product is engineered to conveniently transport and deploy this powerful clay. Granules of sodium bentonite are locked between two layers of geosynthetic textiles, which protect the clay and provide the finished product with the tensile strength and shear resistance needed for handling and installation on slopes.

When the installed GCL is exposed to water, the sodium bentonite core undergoes an incredible transformation. It swells to fill any voids, creating a monolithic, impermeable membrane. This process is far more dynamic than a simple passive barrier like a geomembrane. The GCL possesses a unique self-healing capability. If a minor puncture occurs from a sharp rock or construction activity, the surrounding hydrated bentonite will swell and migrate into the damaged area, effectively plugging the hole and restoring the barrier's integrity.

Construction Preparation: Treating the Base Before Installation

A GCL's performance is only as good as the foundation it rests on. Before any rolls are deployed, the subgrade must be meticulously prepared. This is not a step to be rushed.

- Leveling and Smoothing: The surface must be graded to be smooth and free of abrupt changes in elevation. All sharp objects, rocks, roots, and debris must be removed.

- Compaction: The subgrade must be compacted to a minimum of 85% density. This prevents future settlement that could put stress on the GCL and ensures a uniform contact surface for hydration.

- Surface Condition: The prepared surface should be essentially dry. While a GCL can be installed on a damp subgrade, it must never be laid in standing water or mud. If the groundwater level is high, effective dewatering measures must be implemented before work begins.

- Detailing Corners and Angles: The transitions between the base and any vertical walls or steep slopes should be graded to a smooth curve or a blunt angle. Sharp, 90-degree internal corners create stress points and should be avoided.

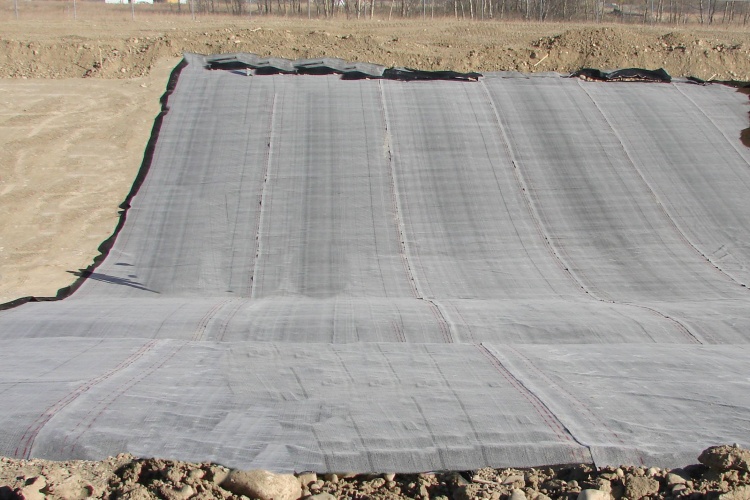

GCL Installation: Laying and Overlapping Procedures

With the subgrade prepared, the GCL panels can be installed. This process must be systematic and follow strict guidelines to ensure a continuous, leak-free barrier. An experienced crew is essential.

Laying Direction:

- On slopes, GCL rolls must be deployed vertically, from the crest of the slope downwards.

- In channels or canals, the panels should be laid parallel to the direction of water flow. This means the upstream panel should overlap the downstream panel.

Overlap Requirements:

This is one of the most critical steps. Adjacent GCL panels must be overlapped to ensure continuity of the bentonite layer.

- The minimum overlap width for all seams is 300 mm (12 inches).

- At the overlap, a continuous bead of granular sodium bentonite powder must be applied along the seam (approximately 0.4 kg per linear meter). This supplemental bentonite ensures a robust, failsafe seal between panels.

The panels should be laid flat and relaxed, without wrinkles. On large, flat areas, it is sometimes recommended to introduce a small, 100 mm "wrinkle" or wave in the panel to accommodate for any minor subgrade settlement or thermal movement.

Anchor Trenches and Slope Stability

When installing a GCL on any slope, mechanical anchorage is required at the top to prevent it from sliding down due to its own weight or the weight of the cover soil. This is achieved using an خندق مرساة.

An anchor trench is a small ditch, typically 300 mm wide and 300 mm deep, dug at the crest of the slope. The GCL panel is extended over the top of the slope and laid down into the trench. The trench is then backfilled with compacted soil. This mechanically locks the top of the liner in place, providing the stability needed for the entire slope length. Seams should never end right at the toe or crest of a slope where stresses are highest.

Quality Control: Preventing Premature Hydration

The absolute cardinal rule of GCL installation is: do not let it get wet before it is covered.

Premature hydration by rainfall is the number one cause of GCL installation failure. If the bentonite core gets wet and swells before the protective cover soil is in place, several problems occur:

- The bentonite swells uncontrollably, losing density and becoming soft and easily displaced.

- Its shear strength is drastically reduced.

- When construction equipment drives over the cover soil, the soft, hydrated bentonite can be squeezed out of the seams, destroying the seal.

- Plan for Dry Weather: Only unroll as much GCL as can be covered with a protective soil layer in the same working day.

- Use Protective Covers: At the end of a workday or if rain is imminent, cover all exposed GCL with waterproof plastic sheeting.

- Inspect and Replace: If a section of GCL becomes prematurely hydrated, it cannot be salvaged. It must be cut out and replaced with new material.

Final Step: Placing the Protective Cover Layer

Once an area of GCL has been laid, overlapped, and inspected, it must be covered immediately. The protective cover layer, typically a minimum of 300 mm (12 inches) of sand or fine-grained soil, serves two purposes:

- It protects the GCL from mechanical damage, UV exposure, and desiccation (drying out).

- It provides the confining stress needed to control the bentonite's swell, forcing it to hydrate into a dense, low-permeability gel.

The cover material must be placed carefully using low-ground-pressure machinery (e.g., a wide-track dozer). Soil should be pushed out over the GCL from the edges, never dumped directly onto the liner. Heavy equipment must never drive directly on an unprotected GCL.

Conclusion: A System Dependent on Clay and Care

A Geosynthetic Clay Liner is an elegant and highly effective engineering solution, harnessing the power of natural sodium bentonite in a versatile, easy-to-install format. Its success, however, is not automatic. It depends first on selecting a product with high-quality sodium bentonite, and second, on meticulous construction practices. By respecting the material's properties—especially its sensitivity to premature hydration—and following the proven procedures for subgrade preparation, seaming, and covering, you can build a containment system that offers unparalleled security and peace of mind.