Clients frequently approach us asking to buy a "membrane gas holder" for their lagoon, but upon reviewing their drawings, I realize what they actually need is a floating cover. Combining these two concepts is the single most common conceptual error I see in B2B procurement for biogas projects. If you treat a floating cover as a pressure-regulating gas holder, your downstream generators will fail, and your safety risks will skyrocket.

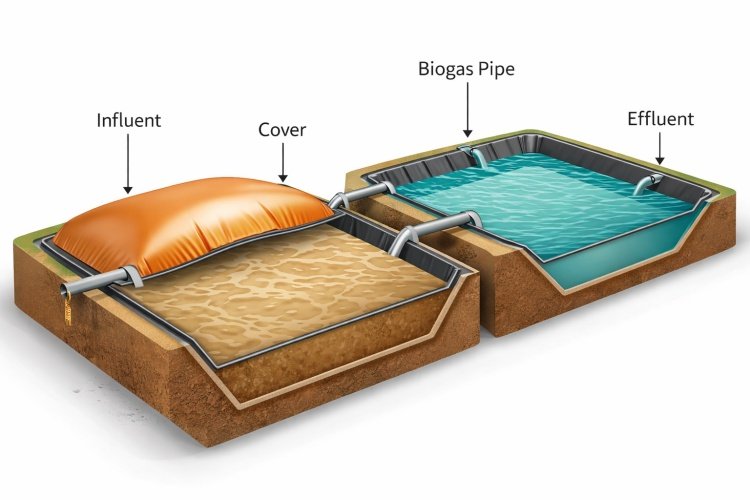

A Biogas Floating Cover is a flexible, gas-tight geomembrane system installed directly on the surface of an anaerobic lagoon or tank. Its primary engineering function is to seal the anaerobic environment and capture methane, not to store gas under constant pressure. It works by passively inflating as gas accumulates and deflating as gas is withdrawn, acting as a dynamic lid rather than a pressurized vessel.

Many facility owners view the black HDPE sheet covering a pond as simply a "lid," but in engineering terms, it is a dynamic biological interface. The moment you seal a huge volume of organic waste under a membrane, you change the physics and chemistry of the site entirely. In this guide, I will strip away the marketing jargon and explain exactly what a floating cover is, how it functions mechanically, and why you must stop confusing it with a gas storage tank.

What Is a Biogas Floating Cover? (The Engineering Definition)

In the geosynthetic export industry, we defined a Biogas Floating Cover fairly strictly to avoid project failures. It is a flexible, impermeable membrane system that floats—either by trapped gas buoyancy or auxiliary floats—on the surface of a liquid digestate. While it looks like a simple sheet, it is an engineered barrier system designed to separate the anaerobic process from the atmosphere.

From a procurement and engineering standpoint, a floating cover is defined by three non-negotiable characteristics:

- Flexibility: It must be able to rise and fall significantly. The liquid level in a lagoon varies, and the gas volume trapped underneath varies. A rigid roof cannot handle this; only a flexible membrane (usually HDPE or LLDPE) can adapt to these volume changes without structural failure.

- Airtight Integrity: Unlike a rainwater cover, a biogas cover must be hermetically sealed. It is not just keeping rain out; it is keeping methane (CH4) in and oxygen (O2) out. Even a tiny pinhole defeats the purpose of the anaerobic process.

- Direct Surface Interaction: The material is in direct contact with the aggressive digestate and the corrosive biogas headspace.

What A Floating Cover Is NOT

I cannot stress this enough: A floating cover is NOT a liner, and it is NOT a gas holder.

А Liner is the bottom layer that prevents liquid from leaking into the soil. It is static and supported by the ground. A Floating Cover is the top layer; it is dynamic, constantly moving, and supported only by liquid and gas pressure.

Furthermore, a floating cover is not a Gas Holder in the sense of a double-membrane gas balloon. A gas holder is designed to provide consistent outlet pressure to a generator. A floating cover provides variable pressure based on how much the membrane is stretched. If you try to run a generator directly from a floating cover without a booster pump or regulator, your engine will likely stall or surge.

The Role of the Cover in the Anaerobic Digestion System

To understand the floating cover, you must visualize where it sits in the hierarchy of a biogas plant. In the projects we supply, we categorize typical lagoon systems into layers. The floating cover generally occupies Level 5 (The Covering System).

The System Hierarchy

- Level 3 (Chemical & Temperature Environment): This is the liquid digestate itself—the "soup" of bacteria, acids, and solids.

- Level 4 (The Containment Structure): This is the earthwork, concrete walls, and the bottom liner that holds the liquid.

- Level 5 (The Covering System): This is the floating cover. Its job is interface management.

- Level 6 (Gas Handling): This includes the piping, flare, and separate storage units.

The floating cover is the shield at Level 5. Its primary engineering role is to create a "biological vacuum." Anaerobic methanogens—the bacteria that make biogas—die instantly in the presence of oxygen. The cover’s first job is not actually to catch gas, but to exclude air. By sealing the surface, we allow the anaerobic biology to thrive.

Problems It Solves in Practice

In my experience dealing with palm oil mills (POME) and starch factories, clients install these covers for three practical reasons:

- Odor Elimination: An open anaerobic pond smells horrific. A sealed cover drops odor emissions by near 100%.

- Safety & Revenue: Instead of venting methane (a potent greenhouse gas and fire hazard) into the air, the cover captures it. This turns a liability into fuel for power generation.

- Temperature Retention: The black membrane absorbs solar heat and insulates the surface, keeping the liquid warmer. This is crucial because methanogens work faster in warm environments. An open pond loses heat rapidly; a covered pond retains it.

How a Biogas Floating Cover Works (The Mechanics)

The operation of a floating cover acts like a "passive lung." It does not have motors or active mechanical parts moving the membrane. Instead, it relies on the physics of gas production and buoyancy.

The Gas Accumulation Cycle

When the digester is active, gas bubbles rise from the bottom sludge to the surface.

- Initial Stage (Flat): When there is no gas, the cover creates a vacuum-like seal against the liquid. This is often called the "suction" phase.

- Accumulation (Inflation): As gas is produced, it gets trapped between the liquid surface and the membrane. Since the edges are sealed, the gas cannot escape. It pushes the membrane upward.

- The "Bubble" Effect: The membrane acts like a giant, low-pressure balloon. The gas naturally migrates to the highest points of the cover. In a large lagoon, you will see multiple "pillows" or humps of gas forming across the surface.

- Extraction: The gas collection pipe system (usually perforated pipes floating under the cover or attached to the membrane) provides a path of least resistance. The slight positive pressure created by the weight of the heavy membrane pushes the gas into the pipes and out to the flare or scrubber.

Sealing Mechanics

How do we keep the gas from leaking at the edges? This is the most critical installation detail. We typically use an anchor trench.

We dig a trench around the perimeter of the lagoon, usually 1 meter deep. The edges of the floating cover are pulled into this trench and buried with compacted soil or concrete. This mechanical lock ensures that even when the cover collects a massive bubble of gas, the edges don’t pull out. In concrete tanks, we use stainless steel flat bars and neoprene gaskets to bolt the cover to the wall, creating a compression seal.

Managing the "Slack"

A working floating cover is never taut like a drum. It must be loose. If you install a cover tight across a pond, the first gas bubble will rip it apart. We calculate a "slack factor"—usually adding 10% to 20% extra material area compared to the flat water surface area. This extra material allows the cover to swell up with gas and move down when the liquid level drops, without stressing the welds.

Typical Component Structure of a Floating Cover

A floating cover is not just a single sheet of plastic. It is a system of welded panels and accessories. In our export projects, roughly 30% of the project cost goes into the accessories and welding, not just the raw membrane roll.

The Membrane Body

The two most common materials we supply are HDPE (полиэтилен высокой плотности) and LLDPE (Linear Low-Density Polyethylene).

- HDPE: The industry workhorse. It offers excellent UV resistance and chemical resistance against the corrosive H2S in biogas. It is stiff and strong. We recommend this for large, open lagoons where the cover is exposed to intense sunlight for 10+ years.

- LLDPE: More flexible and "stretchy." It is better for smaller tanks or regions with extreme temperature fluctuations, as it handles thermal expansion better without wrinkling or stress-cracking.

The Ballast and Weight System

You cannot just let the gas go anywhere. If you do, the wind will whip the inflated cover around, potentially damaging it. We install ballast weights—usually concrete blocks or sandbags filled with gravel—arranged in specific patterns on top of the cover.

These weights create defined channels. They force the gas to flow toward the collection pipes and prevent the cover from turning into a giant sail during a storm. They also help direct rainwater toward pump sumps (more on that later).

Gas and Water Management Ports

A cover needs penetrations, but every hole is a risk.

- Gas Vents: Ensure gas can leave the system.

- Inspection Hatches: Allow operators to sample the sludge or insert mixers without removing the whole cover.

- Rainwater Pumps: This is the most overlooked component. Since the cover floats, rainwater will pool on top of it. If you don't pump this water off, the weight can sink the cover or submerge the gas collection pipes. We install weighted low points (sumps) on the cover where submersible pumps sit to automatically remove rainwater.

Application Scenarios (Where It Makes Sense)

Floating covers are not the universal solution for every biogas plant. In my workflow, I categorize projects into "Low Tech/Large Area" and "High Tech/Compact." Floating covers dominate the first category.

The Ideal Scenario: CSTR and Large Lagoons

The perfect application for a floating cover is a large earthen lagoon or a Covered Anaerobic Lagoon (CAL).

For example, in a starch processing plant in Southeast Asia, the wastewater volume is massive—often tens of thousands of cubic meters. Building a steel or concrete tank for that volume is financially impossible. The only viable solution is a large dug pond lined with HDPE and covered with a floating HDPE cover.

Here, the primary goal is wastewater treatment and volume reduction. The gas production is high volume but low pressure. The floating cover creates a massive, cost-effective reactor vessel.

Low-Pressure Systems

Floating covers are also suitable for Low-Rate Anaerobic Digesters where the gas usage is immediate (e.g., a boiler running continuously). Since the cover doesn't store pressure well, the system works best if the gas is consumed as it is produced, or if there is a separate compressor and storage tank downstream.

Where We Don't Use Them

If your project is a compact, high-solids food waste digester in a city center, a floating cover is rarely the right choice. These sites usually require vertical tanks (CSTR) with double-membrane gas holders mounted on top to save space and provide pressure regulation.

Risk, Limitations, and When This Is NOT Recommended

This is the section where I must protect you from a bad purchase. EEAT principles demand honesty about limitations. As a supplier, I could just sell you the material, but if the application is wrong, you will blame the material when the system fails.

Limitation 1: Zero Pressure Regulation

A floating cover generates almost zero pressure. The only pressure comes from the weight of the plastic sheet itself (which is minimal) and any added ballast weights. This is usually less than 1-2 mbar. Most biogas generators require significantly higher inlet pressure (often 20-50 mbar or more).

The Risk: If you connect a generator directly to a floating cover, the engine will suck the gas out faster than it is produced, creating a vacuum that can suck the cover down into the sludge, damaging the mixers. You должен install a gas blower/booster skid between the cover and the engine.

Limitation 2: Rainwater Vulnerability

In tropical regions (where many of my clients operate), heavy monsoons are a major threat.

The Risk: A floating cover turns into a giant rainwater catchment basin. If your rainwater removal pumps fail or lose power during a storm, tons of water will accumulate on top of the cover. This weight displaces the digestate below, potentially causing the lagoon to overflow its banks. I have seen lagoons breach their dykes because the rainwater weight on the cover pushed the liquid layout to the overflow point. Active management of rainwater pumps is mandatory.

Limitation 3: Difficulty in Maintenance

Once a floating cover is installed and the lagoon is full, you cannot easily see what is happening underneath.

The Risk: If your lagoon fills up with sand or sludge (silting), or if a mixer breaks, you cannot access it without removing the cover or sending in hazardous duty divers. Unlike a steel tank with a side hatch, a covered lagoon is a "black box." You need rigorous pre-treatment (sand removal) before waste enters the lagoon to prevent it from filling up with solids.

Common Misunderstandings & Engineering Clarifications

There is a recurring confusion in the industry between "collection" and "storage." Let's clear this up using the "Floating Cover vs. Gas Holder" debate.

Misunderstanding: "The floating cover is my gas storage."

Clients often calculate the volume under the inflated cover and assume they can store that much gas for use later (e.g., to run a generator only during peak hours).

The Reality: While a floating cover does hold volume, it is not reliable storage. As the gas volume drops, the heavy plastic sheet sags. This sagging creates folds and pockets where gas gets trapped and cannot reach the outlet pipe. You might theoretically have 1,000 m³ of space, but only be able to effectively extract 600 m³ before the cover blocks its own outlet.

Additionally, as the cover deflates, the pressure drops to zero. A true gas holder uses an inner membrane (gas) and an outer membrane (air) to maintain constant pressure regardless of volume. A floating cover cannot do this.

Clarification:

- Floating Cover: Design Goal = Covering & Collection. It isolates the liquid and funnels gas to a pipe.

- Double Membrane Gas Holder: Design Goal = Storage & Buffering. It holds gas at a set pressure for stable downstream use.

If you need to store gas for 8 hours to run a generator during the night, buy a standalone Double Membrane Gas Holder. Do not rely on the lagoon cover.

Заключение

А Biogas Floating Cover is the most cost-effective solution for sealing large anaerobic lagoons and capturing methane. It functions as a flexible, passive lid that inflates with gas production and relies on airtight welding and proper ballast weighting to operate safely.

However, it is vital to remember its role in the system: it is a Covering System , not a high-tech storage tank. It excludes oxygen effectively and mitigates odors, but it offers poor pressure regulation and requires active management of rainwater.

If you are planning a large-scale wastewater project, a floating cover is likely your best option. But if you need precise gas buffering for complex power generation, you must pair this cover with a proper gas handling system or a separate storage holder. Don't ask the cover to do a job it wasn't built for.