Every landfill produces a toxic liquid called leachate, a cocktail of chemicals and contaminants. If this liquid escapes, it can poison our groundwater for generations. So, how do we build a structure that can safely contain this hazardous waste for decades?

This guide explains how a modern landfill bottom liner system works as a multi-layered defense to protect groundwater. I will break down each critical component, from the geomembrane to the clay, and show you how they work together to prevent pollution and ensure long-term environmental safety.

As a supplier of geosynthetics for these projects, I know that a liner is much more than just a plastic sheet. It is a sophisticated, engineered system. Understanding how it functions is the first step to ensuring it is built correctly.

Introduction: Why Groundwater Protection Matters in Landfills

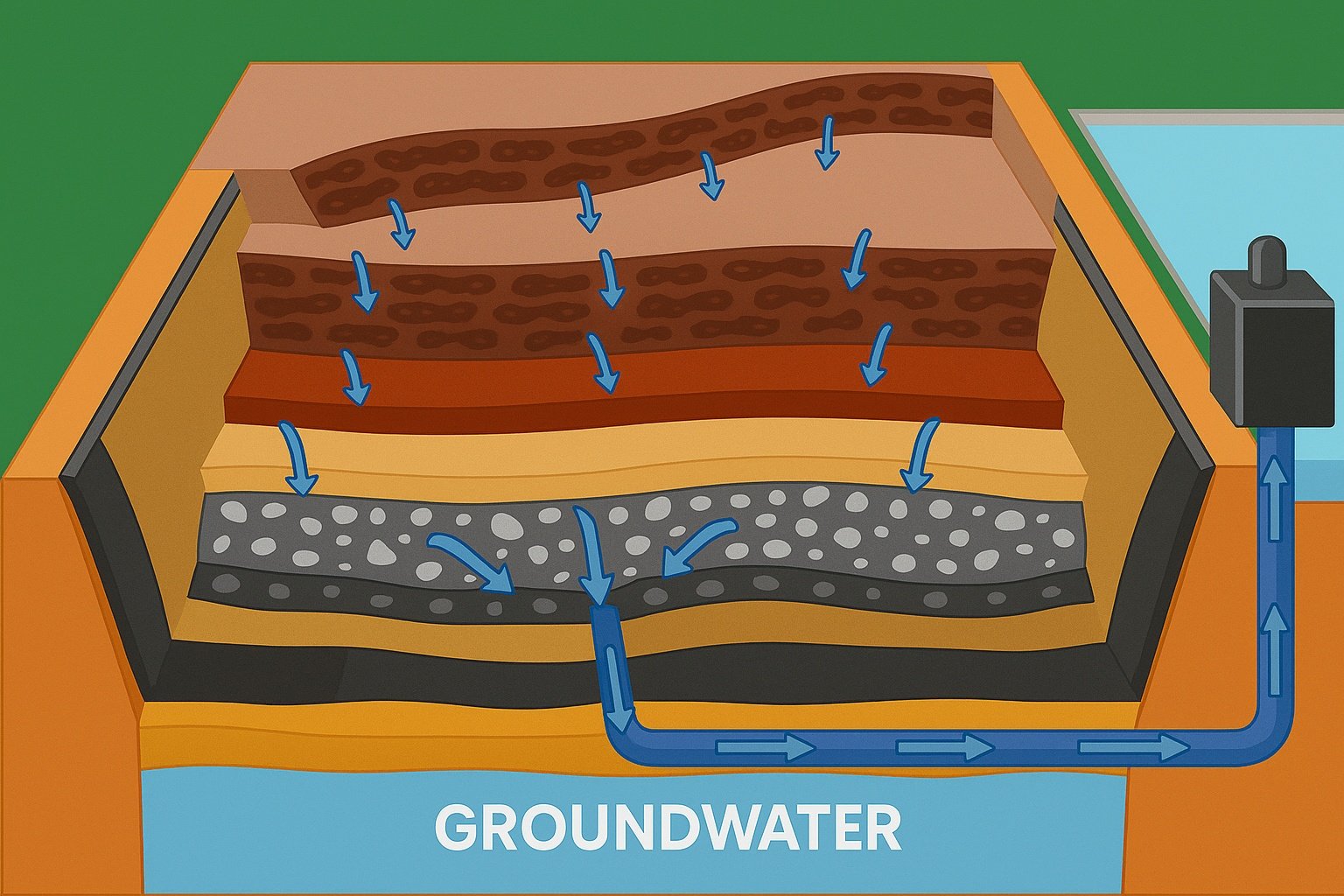

The primary environmental risk associated with any landfill is the contamination of groundwater. When rainwater filters through the waste, it picks up dissolved and suspended materials, creating a highly contaminated liquid known as leachate.

Leachate can contain heavy metals, ammonia, organic compounds, and various other pollutants that pose serious public health risks. If it seeps into the ground and reaches the water table, it can render local water sources unsafe for drinking, agriculture, and industry for a very long time. The entire purpose of modern landfill engineering is to create a robust containment system that prevents this from happening. This system must be designed to perform reliably for the entire active life of the landfill and for many decades after its closure. The bottom liner is the most critical element of this containment strategy.

What Is a Landfill Bottom Liner System?

A landfill bottom liner system is an engineered barrier constructed at the base of a landfill before any waste is placed. Its job is to separate the waste and leachate from the underlying soil and groundwater. Think of it as a giant, high-performance bowl designed to be completely impermeable.

For those less familiar with the engineering details, the basic function is easy to understand. The liner system is designed to do two things:

- Contain: It provides a physical barrier that stops leachate from migrating downwards into the earth.

- Collect: It incorporates a drainage system that gathers any leachate that forms and directs it to a collection point for proper treatment.

By preventing escape and enabling collection, a properly designed and installed liner system effectively isolates the landfill's contents from the surrounding environment, forming the cornerstone of modern, safe waste disposal.

Key Components of a Landfill Bottom Liner System

A modern landfill bottom liner is not a single layer but a composite system of several different materials, each with a specific function. From the ground up, these layers work together to create a powerful, multi-layered defense.

Prepared Subgrade Layer

This is the very foundation of the liner system. Before any geosynthetics are placed, the native soil is carefully excavated, graded, and compacted to create a smooth, stable, and strong base. This layer must be free of sharp rocks, roots, or voids that could damage the overlying liners. In many advanced designs, we also build a groundwater drainage layer on top of this subgrade, often using a thick layer of gravel (≥1.0m). This critical layer intercepts any groundwater that might try to well up from below, preventing hydraulic pressure from pushing against and potentially damaging the liner system.

Zbijena glinena obloga (CCL)

The first true barrier layer is often a thick layer of compacted clay. This isn't just regular dirt; it's a specific type of clay with very low permeability, meaning water moves through it extremely slowly. A typical specification requires a thickness of at least 0.5 meters and a permeability coefficient no greater than 1x10⁻⁹ m/s. At this rate, it could take years or even decades for liquid to pass through. This layer acts as a robust secondary barrier and has the added benefit of being able to chemically adsorb and attenuate certain contaminants.

Geomembrane Liner (HDPE)

This is the primary barrier and the component people most often think of. It is a thick sheet of plastic, almost always High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE), with a thickness of at least 1.5 mm. HDPE is the material of choice because it is incredibly strong, durable, flexible, and highly resistant to the wide range of chemicals found in leachate. While the clay liner is a hydraulic barrier that slows down flow, the HDPE geomembrane is a true physical barrier, designed to be completely impermeable.

Leachate Collection and Drainage Layer

Placed directly on top of the HDPE geomembrane is a thick drainage layer, usually made of gravel, geonet, or a network of perforated pipes. Its purpose is to collect any leachate that forms and quickly channel it away to a sump or collection point. This is critical because it prevents the buildup of liquid pressure (or "leachate head") on the liner. Regulations often require that the liquid depth in this layer never exceed 30 cm, as high pressure could force leachate through any potential small imperfections in the liner.

Zaštitni pokrovni sloj

Finally, a protective layer is placed on top of the drainage system before the waste. This is typically a geotextile fabric or a layer of select soil (≥0.3m thick). Its sole purpose is to protect the underlying components—especially the critical HDPE geomembrane—from being punctured or damaged by sharp objects in the first layer of waste or by construction equipment during operation.

Types of Landfill Bottom Liner Systems

While the components are similar, they can be configured in different ways depending on the type of waste being managed and the level of environmental risk. The design can range from a simple single liner to a highly secure double liner system.

Single Liner Systems

A single liner system consists of just one primary barrier, which might be a geomembrane or a layer of compacted clay. These are generally considered outdated for municipal solid waste and are typically only used for landfills containing inert waste like construction and demolition debris, where the risk of generating harmful leachate is very low. Their main limitation is the lack of redundancy; any defect or damage results in a direct leak into the environment.

Sustavi kompozitnih obloga

This is the most common design for modern MSW landfills. A composite liner combines a geomembrane (like HDPE) placed in direct contact with a low-permeability soil layer (like a CCL or a Geosynthetic Clay Liner). This combination is far more effective than either layer alone. The geomembrane provides the primary barrier, but if it has a small pinhole or defect, the underlying clay layer prevents leachate from spreading out, dramatically restricting the leakage rate. Studies show that a composite liner can be hundreds of times more effective at preventing leakage than a single geomembrane or a single clay liner.

Double Liner Systems

For landfills containing hazardous or highly toxic waste, an even higher level of protection is required. A double liner system features two complete composite liners separated by a drainage layer. This design provides maximum security and redundancy. The upper (primary) liner contains the waste, while the lower (secondary) liner acts as a backup. The space between them, known as the leak detection zone, is monitored constantly. If liquid is ever detected in this zone, it signals that the primary liner has been breached, and corrective action can be taken long before any contaminants reach the environment.

How Bottom Liners Protect Groundwater

The protection offered by a bottom liner system is not based on a single mechanism but on a multi-pronged defense strategy that combines physical, hydraulic, and chemical principles.

The first line of defense is collection and control. The leachate collection system quickly removes the bulk of the liquid, minimizing the time it is in contact with the liner and reducing the hydraulic pressure that drives leakage.

The second defense is physical and hydraulic prevention. The HDPE geomembrane acts as a near-perfect physical block. However, acknowledging that tiny installation defects or pinholes are statistically possible, the underlying compacted clay liner provides a powerful secondary hydraulic barrier. Leachate that might escape through a small hole in the geomembrane is immediately met by the clay, which allows liquid to pass through only at an incredibly slow rate. This synergy is key: the leak through the composite system is much, much smaller than a leak through either layer individually.

The final defense mechanism is chemical attenuation and delay. As leachate slowly percolates through the compacted clay layer, many contaminants are physically and chemically bound (adsorbed) to the clay particles. This is especially true for organic pollutants. This process not only removes contaminants from the liquid but also dramatically slows their migration. Conservative ions might take over 50 years to pass through a composite liner, by which time their concentration has been significantly reduced through decay and dispersion.

Common Materials Used in Bottom Liners

The long-term performance of a liner system is entirely dependent on the quality and properties of the materials used. Specific geosynthetics and soils are chosen for their unique characteristics that make them suitable for a harsh landfill environment.

HDPE Geomembranes

High-Density Polyethylene is the industry standard for the primary geomembrane liner.

- Advantages: It has exceptional chemical resistance to the aggressive compounds found in leachate, high tensile strength, and excellent durability against UV exposure and weathering during installation. It can be reliably seamed together on-site using thermal welding techniques to create a continuous, leak-proof barrier.

- Disadvantages: It can be susceptible to stress cracking under certain conditions and can be punctured if not properly protected. Quality control during installation is absolutely critical.

Clay-Based Liners

Compacted clay liners (CCLs) are the traditional choice for the secondary barrier.

- Advantages: Clay is a natural material that provides a low-permeability barrier and has excellent properties for attenuating contaminants through adsorption. When properly hydrated, it can also self-heal minor cracks.

- Disadvantages: Construction can be challenging. It requires a suitable source of clay nearby, and performance is highly dependent on achieving the correct moisture content and compaction level, which can be difficult in adverse weather conditions.

Geosynthetic Clay Liners (GCLs)

GCLs are a modern alternative to thick compacted clay liners. They are factory-manufactured composites consisting of a thin layer of high-swelling bentonite clay sandwiched between two geotextiles.

- Structure and Mechanism: When a GCL gets wet, the bentonite clay hydrates and swells to form a low-permeability barrier equivalent to a much thicker layer of compacted clay.

- Prijave: GCLs are often used in composite liner designs directly beneath the geomembrane. They provide excellent performance with faster, more consistent installation compared to building a traditional CCL.

Regulatory Requirements and Design Standards

Landfill design and construction are tightly regulated by environmental agencies around the world. These regulations set the minimum standards for liner system performance to ensure groundwater is protected. While specific rules vary by region, they generally dictate key performance criteria.

These criteria often include:

- Minimum thickness for geomembranes (e.g., 1.5 mm or 60 mils).

- Maximum allowable permeability for clay liners (e.g., 1x10⁻⁹ m/s).

- Requirements for leachate collection system efficiency (e.g., maintain leachate head below 30 cm).

- Mandatory use of composite or double liner systems depending on the waste type.

As a supplier and project partner, ensuring that all materials meet or exceed these regulatory standards is a fundamental part of our responsibility. Compliance is not just about following rules; it's about guaranteeing the long-term safety and environmental integrity of the facility. Choosing materials from reputable manufacturers with extensive testing and certification is the first step in a compliant and successful project.

Potential Failure Risks and Quality Control Measures

Even the best-designed liner system can fail if it is not installed correctly. The construction phase is the most critical period for ensuring the long-term integrity of the landfill. A rigorous Construction Quality Assurance (CQA) program is essential.

Common causes of liner failure include:

- Punctures and Tears: Damage from sharp objects in the subgrade, careless equipment operation, or unprotected waste placement.

- Poor Seaming: Improperly welded geomembrane seams can create leaks. Seams are the most vulnerable part of the liner and must be tested meticulously.

- Clay Liner Defects: Improper moisture content or insufficient compaction can create high-permeability zones within a CCL.

- Excessive Stress: High differential settlement of the subgrade can put too much strain on the geosynthetics, leading to failure.

To mitigate these risks, a CQA plan must include constant supervision and testing. This involves ensuring the subgrade is perfectly smooth, testing every inch of geomembrane seam using methods like air pressure or vacuum box testing, and verifying the density and moisture of every lift of compacted clay. Long-term monitoring, often with leak detection systems, continues this quality control for the entire life of the facility.

Conclusion:

A landfill bottom liner is a sophisticated, multi-barrier system that stands as our primary defense in protecting precious groundwater resources from contamination. Through a combination of leachate collection, physical barriers, hydraulic resistance, and chemical attenuation, these systems are engineered to provide safe and secure waste containment for generations. Proper design, high-quality materials, and meticulous installation are all equally critical for success.